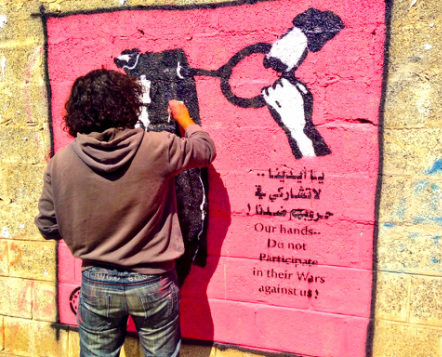

Murad Subay, 7th Hour, Twelve Hour Campaign, Sana'a Murad Subay, 7th Hour, Twelve Hour Campaign, Sana'a He is painting graffiti on a wall opposite a westernized shopping mall. All major media networks are there, Reuters, Al-Arabiya, Agence France Presse, they try to capture his attention as they are buzzing around him: “Murad, here please,” “Murad, Murad!,” “Hello Murad, can you explain what you doing;” a fixer approaches him as he tries to concentrate: “Murad, my client would like a bit of time to interview you later, can you make it?”… If twenty-seven year-old Murad Subay is a star, he does not behave like one. He does not see the circus going on around him as a disturbance, he embraces it and makes it part of his work. A self-made artist, he is painting to raise awareness on certain issues, and he channels the attention from his own person to the message he is trying to spread, both locally and globally. It is clear, vivid, uncompromising: two hands hold a hand-grenade circular safety pin, ready to undo it, a sentence is written both in Arabic and English “Our hands… Do not participate in their wars against us.” It all started in 2011, after the civil war that opposed dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh and other tribes, an offset of the “Arab Spring” which could well have transformed Yemen into another Syria. As opposed to Syria, the Yemeni dictatorship was backed by the US, and only a cosmetic change occurred: Saleh’s Prime Minister was elected in office with 99.6% of the vote.(1) Murad explains: “the city bore the scars of the clashes, so I went out and started to paint over them. After one week, people started to come and paint with me. Parents sent me their children, even soldiers put their weapons down and took brushes instead.” The Color the Walls of Your Street campaign was born. After to months, all major cities in Yemen took the initiative, colors appeared in Aden, Ta-az, Ebb, and Hodeidah. The campaign received international coverage, and was very well received by the Yemeni population. As Murad learned stencil art, his second campaign was planned. For some, it took a political turn, yet Murad stresses that it is not his aim: “we are not politicians and we don’t have power to stop what is happening to our country. The only thing we can do is making noise around important issues.” During seven months, every Thursday, faces of people “disappeared” by the government, some since the 1960s, were painted all over Sana’a and other towns. Next to the faces, the date of the disappearance, and the idea that no one can vanish from public view. Walls became a symbol of hope, of unity, not only for the disappeared but also their families, which were brought at the core of public spaces. The Walls Remember Their Faces campaign had a decisive impact. Maybe the US embassy asked that its puppet "ally" throw a bone to its people… Four months after the campaign started, Mutar Aleriani was released. He had been disappeared since 1981. He was tortured so badly with a drill that he can no longer move his legs. Confined to a wheelchair, he is not being looked after by his daughters. Murad met him in Hodeidah, his words against US ally Abdullah Saleh were understandably very harsh. Murad explains how the campaign has brought humanity onto the whole issue; meeting Mutar had a huge impact on him. Murad realizes that he cannot design a campaign for all the issues that Yemen is facing right now. He is not financed, and rejects all offers of help from international organizations, including the UN. He says that he needs to remain independent, so that the impact of his campaigns cannot be compromised: “the supplies could be coming from [not so benevolent neighbors] Saudi Arabia or Iran, we just cannot allow that.” Everyone who turns up brings their own supplies, and people who are part of the network also donate items randomly. Murad is his own complex adaptive system.(2) Paintings speak louder than academic lectures. Murad’s Twelve Hour campaign is now famous around the world for its coverage of the drones issue. A little boy writes right below a drone: “why did you kill my family.” This question is timely: many children in Yemen are asking themselves the question, day in, day out. Chances are that Westerner meeting them will be asked, just like I was.(3) Another painting by Hadel Almowafak represents a Tao symbol, on top the drone, and at the bottom a dove: the vivid imagery of Liberal Peace, the peace that kills innocents, the peace that I teach as pat of the UN. The drones representations figure in Murad’s Twelve Hours Campaign. Each hour of a clock brings in a new issue that Yemen is facing: weapons, sectarianism, kidnappings, poverty, and internal strife. Will one of the hours focus on Barack Obama’s war secret war against Yemen?(4) Murad’s stencils ought to reach the streets of Washington, D.C., New York and San Francisco, so that Yemenis would no longer be disappeared from the world’s view.(5) We often ask ourselves what we can in the face of injustice. Murad gives us a plain answer: noise. (1) See http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/25/world/middleeast/yemen-to-get-a-new-president-abed-rabu-mansour-hadi.html, accessed on January 20th 2014. (2) See Decolonizing Peace, chapter 3. (3) Please circulate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un0vxahkYFM (4) See http://dirtywars.org (5) For more information on Murad Subay and Hadel Almowafak, see: http://muradsubay.wordpress.com and http://hadeelalmowafak.wordpress.com

2 Comments

Abdul Rahman Ali Barman in HOOD's Office, Sana'a Abdul Rahman Ali Barman in HOOD's Office, Sana'a Abdul Rahman Ali Barman is a Yemeni lawyer dedicated to human rights. His organization, HOOD, is active since 1998, and has seen many cases over the years. In a dictatorship, the amount of threats that such an NGO receives from the government is always a testimony to its efficiency. In 2011, HOOD’s central office in central Sana’a received direct cannon rounds from a nearby army barrack: they must have been doing something right. They continued their work from a tent for over a year and a half, and are now back to their headquarters processing all sorts of human rights violations. Abdul Rahman says that since the removal of President Saleh and the subsequent landslide victory of his former deputy Abd Rabu Mansour Hadi, not too difficult to obtain since he was the only candidate, things are looking up in Yemen. There are improvements in some areas such as press and internet freedom, people are becoming more free to share their ideas, up to a certain point of course. There are still enforced disappearances and random arrests of journalists. Guilt by association prevails in Yemen, where the suspicion of any link with al-Qaeda can land someone in prison. There, the interrogation techniques have not changed. After all, democracy is a lengthy process, it requires time to hatch, or so we are told by Liberal Peace fairy tales. Detainees are still subjected to the same type torture as before the Arab Spring: electricity, suspension of arms twisted behind the back, punching, etc. Why is the human rights situation in Yemen so important, and what is the connection to drone strikes and targeted killings carried out by the US government on Yemeni soil? From an International Law perspective, there are two different frameworks that could apply, depending on whether the US has declared war against another Nation State. If it has, there are rules on how to conduct a war with a minimum damages, under the precepts of International Humanitarian law. If it has not, the use of lethal force is much more difficult to justify, and falls under the precepts of International Human Rights Law. From the perspective of the latter framework, the practice of targeted killings could be regarded as an extrajudicial execution. That’s however not counting with the help of the United Nations Charter. Under its article 51, a country can kill if is has an “invitation from the state where force is used to join with it in armed conflict hostilities.” (1) The US claims that the Yemeni government has asked its help against al-Qaeda, and that therefore Article 51 applies. Abdul Rahman strongly disagrees, and explains that there have been several debates in parliament about this: “how can a country which is not even a democracy ask for this help? The Parliament never requested anything, or passed any law regarding this supposed assistance. No one has access to any documents of the sort. Even the current Prime Minister declared on al-Jazeera never to have seen such documents.”(2) Article 51 cannot work for two reasons. First, the assertion that the current Yemeni leadership was “elected”, in a sad excuse for a democratic process, since there was only one candidate to vote for. Abdul Rahman argues that therefore is no legitimacy to be found in the current government. Second, there was no official request, validated by Parliament, for any military assistance from the US. From an International Human Rights Law perspective, the Obama administration is therefore carrying out extrajudicial executions. Who benefits from this War Crime? Certainly not only the usual suspect, i.e. the Yemeni government. Abdul Rahman mentioned the recent execution of two moderate al-Qaeda officials killed in drone strikes, Fadel Qasr and Mohammed el-Hamda. According to him, Qasr and el-Hamda were members of the AQAP council, the Shura, which decides on operations across the country. They both had withdrawn during the vote on several operations, which they did not agree with. Their names and locations were conveniently given to the Yemeni government to facilitate a purge within AQAP. According to Abdul Rahman, AQAP’s military leader, Qasm al-Raimi, is actually very close to the previous and current governments. Indirectly, the US government is therefore aiding and abating AQAP, assisting in its purge from the inside. Moderates have never made convenient enemies. Can NGO workers too become enemies of the US? Abdul Rahman does not discard the possibility. Last December, Abd al- Rahman Omair Al Naimi, a Qatari colleague from HOOD’s sister organization Alkarama, was designated as a supporter and financier of al-Qaeda by the US Treasury Department. It seems that working on drones and human rights in Yemen may land anyone, author included, in trouble. Abdul Rahman explains that when it comes to these issues, and the power that the US has on the government, these activists could even end up in prison. HOOD and AlKarama’s links with international NGOs such as US-based Code Pink have granted them protection both in Yemen and abroad to a certain extent. However, Abdul Rahman sees these organizations’ lavish spending on the back of their suffering with much caution. He explains: “if they invested even three percent of the funding they obtain thanks to our suffering to help us train Human Rights delegates on the ground, this would enhance our efficiency tremendously.” The Peace Industry as well as free-lance journalists revels on the drones “story,” any other international coming to Sana’a to work on the issue is likely be ignored by the “specialists.” The drones also created a certain gold rush. Alkarama designates the US extrajudicial killings as a second-generation Guantanamo. Abdul Rahman confirms this as many of the targets of US strikes are former prisoners. The most infamous of the attacks, on the town of Majella, fits this profile. On December 17th 2009, the US carried out a “double tap” on a small village nine hours of Sana’a. It killed up to forty-two people, most women and children. This “double tap” technique is notoriously used by al-Qaeda in Iraq or in Afghanistan. It consists of a first strike followed by a second attack a few minutes later, under the understanding that the people rushing to the scene to help others are guilty by association and therefore deserve to die too. In Majella, the first strike consisted of four Hellfire missiles, followed a few moments later by a Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (BGM-109D) “designed to carry 166 cluster bombs, each containing approximately 200 iron splinters that can reach a distance of 150 [meters] from the drop point.”(3) The target of the attack was Mohammed al-Qazimi, a former alleged al-Qaeda associate who had spent fie years in a Yemeni jail, and had been released shortly before the strike. Since he had returned to Majella, he passed an army checkpoint morning and afternoon to go and buy his daily bread and khat.(4) He could easily have been arrested and tried at any time. What therefore justified the strike, and the lavish spending of US taxpayer funds to kill someone who was completely accessible to Yemeni law enforcement? Given the price of the ammunition used, the attack cost a minimum of two million US Dollars, a sum that could easily have been invested in the development of the village, hence fostering pro-US sentiment among the population. After the Majella attack, President Saleh rang the mayor to justify the killing, arguing that all involved, including the women and children, had ties to al-Qaeda. The mayor allegedly responded: “I hoped that when they had died, the children would have known how to read and write; I hoped that when they had died, their stomachs had been full; I hoped that when they had died, they would have had electricity, computers and access to internet.” The attack whose funds could have been put to good use boosted AQAP support in the region. Abdul Rahman recalls the funeral of Majella victims with emotion, especially this old lady who pleaded, referring to the US: “they even have laws that protect animals, why can’t they just consider us like their animals?” (1) See http://law.wustl.edu/harris/documents/OConnellFullRemarksNov23.pdf, p.1. (2) Interview with Abdul Rahman Ali Barman, January 9th 2014, Sana’a, Yemen. (3) See http://en.alkarama.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1157:yemen-license-to-kill&catid=66&Itemid=215, p. 66 (4) The khat is a local leaf that is chewed daily for its stimulant properties.  Anti-drone mural by Hodey Al-Mowafak, Sana'a Anti-drone mural by Hodey Al-Mowafak, Sana'a Farea al-Muslimi sees himself as a friend of the United Sates. Born and raised in Wessab, a village nine hours of Sana’a, and one of twelve living siblings, he was destined to be a farmer. When he was in 9th grade, he obtained his first State Department scholarship to study English, and soon ended up in California as part of the Youth and Exchange Study program, geared towards strengthening friendship between the US and Muslim countries. All went according to plan, Farea soon rose to the top of his class, he visited lots of churches, attended countless barbecues and, cherry on the cake, found a second father in a US Air Force service member. Farea’s State Department-engineered American Dream could not have become more complete. He returned to the Middle East to be awarded yet another scholarship at the American University of Beirut. He was programmed to be one of those countless “local” ambassadors that roam around peace, development or human rights conferences, making excuse upon excuse for the war crimes of Western powers, the North-South divide, or the unequal power dynamics between their neo-colonial masters and the subaltern rest. Malcolm X could have seen Farea as a picture-perfect house-Muslim, catching a cold whenever his master would sneeze. Not quite… Farea’s own village was targeted by a strike on April 17th 2013. On that day, four people were killed. The target was Al-Hadidi al-Radami, a social worker suspected of having ties with Al Qaeda in the Arabic Peninsula (AQAP). As the village mediator, he was actually very close to local authorities. He had returned to the village in 2011 after being imprisoned for fighting against the US in Iraq. Since his return, some political opponents of the Saleh regime both in Wessab and Sana’a to enquired to the police about him, only to be told that he was a reformed character, a pillar of the community. According to them, he had paid his debt to society and deserved to live a peaceful life. This did not prevent him from being put on a target list. According to villagers, Wessab had been observed by drones for well over a year. Farea tried to make sense of the attack. Why wouldn’t the suspect be arrested, interrogated, and tried? Why did local people have to die with him? Why would his village be subjected to the terror of a drone attack? What would warrant such a targeted killing? According to the National Defense Authorization Act of 31 December 2011, one does not need to be part of any group to be the victim of targeted killings: guilt by association, under the clinical term ‘associated forces’ is enough. Farea explains that there are four types of targeted killings, the first two including drones only. Under Type One, President Obama provided four clear conditions for a killing to take place: the person has to be designated as a person of interest under US law; he or she must represent a direct threat to the US; the target cannot be captured; and, finally, the operation must not target civilians. The attack on Wessab clearly does not meet any of those criteria. It was carried out nonetheless. Type Two, which could well have applied, is the “signature strike”, whereby any high ranking military officer as well as President Obama can order the death of a anyone displaying suspicious behavior. Now there is a problem right there: “what is suspicious behavior in the US is completely normal behavior here,” explains Farea, “[it] can represent every single Yemeni in Yemen: if I am with you, going to a wedding outside Sana’a, we will obviously be between the age of 15 and 65, we will be carrying guns [they are part of the Yemeni dress code], and we will be a group, [that’s] enough! It is not even intelligent criteria anymore.” Farea calls this state terrorism, and he is afraid that it is going to get worse. He testified before the US Congress Judiciary Committee six days after the attack on Wessab, and so far, nothing has changed. He says that the logic behind the strikes is devoid of common sense, and that it actually encourages more support for AQAP on the ground. Since the US is becoming its enemy, and terrorizing the population while its puppet government does not react, it cannot end well for any party involved. At present, AQAP is actually much more politically savvy than the US, it has paid compensation to the owner of a house destroyed by a drone strike. Since the US nor the Yemeni government compensate civilians after strikes, this can win many hearts and minds. Farea was educated in the US. He can put himself in anyone’s shoes, and right now, he is a bridge between increasingly estranged nations. He says that the strikes have changed fabric of his own society: ‘if a mother wants to scare her child into going to bed, she used to say that she would call a dad, now she says that she will call the drones.” If at all possible, it will undoubtedly take more than a couple of scholarships to reclaim the hearts and minds of those children’ generation.  Mohammed al-Qawli showing his brother's car Mohammed al-Qawli showing his brother's car Mohammed al-Qawli, a former Headmaster in his late forties, has been restless for nearly a year. On January 23rd 2013, his brother, schoolteacher Ali Ali al-Qawli, was killed in a drone strike, alongside seven other men. They were traveling to the north of the village of Qawlan, half an hour from the Yemeni capital Sana’a, when four hellfire missiles hit their Toyota Hilux. Mohammed remembers hearing an explosion: he went out to see if the Hilux was still in the village, and that’s when he realized that something bad might have happened. He knew about drone strikes but discarded the possibility. The Americans had never targeted his area, notoriously close to the previous government elite. He and other village members travelled to the scene of the explosion: nothing could have prepared them for what they were about to see. The scene was on fire, filled with charred human remains and debris. The car had been moved 10 meters away from the impact of one of the missiles, close to a house on the other side of the road. Water was gushing from an irrigation tube, and men from a nearby village were walking aghast among the debris. Mohammed was on autopilot. Villagers pointed to a charred body at the back of the car, whose teeth were unmistakably those of his brother. Soon, security services turned up. All the officials cared about was to find the car’s number plates. They soon departed the scene. Afterwards, onlookers gathered all the remains they could find: more than one hundred. They were immediately taken to Sana’a for a forensic examination. Immediately after the strike, the Yemeni government declared that al-Qaeda operatives had been killed in the attack. This generated a massive protest from the local tribes, the government was forced to issue a retraction: Ali al-Qawli and all other occupants of the car were declared innocent of any crimes. Since Ali was a quiet schoolteacher with no links to any political organization, Mohammed started asking himself who else in the car could have been targeted. That’s when it dawned on him: a known opponent of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh was in the car, Rabieh Hamud Labieh. Labieh, a democratically elected local councilor, had turned against Saleh during the 2011 Arab Spring-related demonstrations. He was notorious for having denounced the smuggling of government weapons between Sana’a and Saleh’s fief, right after his demise. He had been an opponent to the new regime, arguing that th country was still a dictatorship. According to the Yemeni National Organization or Defending Rights and Freedoms (HOOD), the Yemeni government has been instrumental in assisting the US government with its strikes, from the collection of incriminating “evidence” to the collection human intelligence. In sum, the Yemeni government says who to strike, where and when. For Mohammed, it makes no doubt that the government used the US to get rid of its political opponent, a view shared by HOOD and Swiss-based NGO Alkarama. Not only is the “war on terror” not nearly over, but also one can conclude that the Arab Spring never really took off in Yemen, where Saleh’s successor, former vice-president Abd Rabu Mansour Hadi, continues to purge his political opponents. How much does it cost, in Yemen, to dispose of a democratically elected politician? One only needs powerful allies. Alkarama asserts that it would have been very easy to arrest Labieh and try him for treason. After all, there was a military police checkpoint only five hundred meters from the scene of the explosion. Four Hellfire missiles were launched at Labieh’s vehicle, preceded by more than a day of drone reconnaissance. Provided that the basic cost of a Hellfire is $65,000, counting the drone flying hours and personnel costs, the attack could have reached a $400,000 price tag for the US taxpayer. Since the Yemeni government cleared all occupants of any relationship with al-Qaeda after their death, this particular incident is proving to be a costly mistake. No compensation was offered to the families of the victims. Salim, the car’s driver, left behind an impoverished extended family. Ali left three ophans who are now being raised by Mohammed. Ali’s eldest, Mohammed Ali, asked me to film him as soon as I arrived in his house. He asks a very simple question to President Obama: “Sir, why did you kill my dad?” (1) As we parted, Mohammed says that he will never let go until he obtains an apology from the US government, and compensation for all its Yemeni victims. Whenever there is an attack elsewhere in the country, he races to the scene in own SUV, bought specifically for this reason. He then collects the remaining parts of the missiles and brings them to Sana’a. He has been documenting every strike since his brother’s death, and wows to do so until a missile strikes him eventually. Showing me part of a Hellfire that killed his brother, he defiantly claims: “this is the humanitarian aid we in Yemen get from the US, it is all one big lie, and I will never give up for all the victims’ sake.” (1) See the link to Mohammed Ali al-Qawli's question to President Obama: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un0vxahkYFM  Abdul Al Salam's younger brother Nabil Abdul Al Salam's younger brother Nabil Here is a cautionary tale for anyone out there working in intelligence, whether as a mere asset or a field operative. When your government is trying to get rid of you, what better cover but to accuse you of having links with al-Qaeda? One certainly can assert that Abdul Al Salam al Hilal had "ties" with al-Qaeda. It was in 2002, and he had been working for Yemen’s internal intelligence services for a while. In his early thirties, he was a “field” contact person for former Yemeni detainees who had returned from Afghanistan. His job was to monitor them and make sure that they would remain politically quiet after their return. The dictatorship of President Ali Abdullah Saleh was very close to the US government at the time, and an active ally in the “war on terror”. As he was in Egypt for a business trip, his day job was with a construction company; Abdul Al Salam was arrested and transferred to a prison where he remained for one and a half year. He did not know why he had been arrested and kept being asked about his involvement with al-Qaeda. He claims to have been tortured by Oman Suleiman in person, then head of the Egyptian Intelligence Services. In 2004, he was transferred to Bagram airbase and soon after shipped to Guantanamo. He has been there ever since, claiming his innocence among another ninety detainees from Yemen. While his family managed to make sporadic contact with him through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), they have no idea what his current situation is. They say he has been punished for a while, they don’t know why. Before the loss of contact, Abdul Al Salam wrote that there had been two assassination attempts made against him in Guantanamo. He also communicated to his family that they should never believe news of his possible suicide. In a Skype conversation organized by the ICRC, he said: “I will not commit suicide, don’t believe any of it. I know I am innocent. This is all game that is much bigger than me.” Was Abdul Al Salam sold to the US government, as his family seems to think? Was the information that he had so valuable that he deserved to be removed from the land of the living? In 2008, his two boys Omar, 11, and Yussef, 8, opened the safe where he was storing all the documentation related to his intelligence work. Due to the sensitive nature of his files, it was was booby-trapped. Both children died instantly. It was then up to his older brother Abdu Rahman to break the news to him, via the ICRC. Since the call was on humanitarian grounds, it lasted for two hours, and was overseen by a religious Imam. Abdul Al Salam was devastated. After costing him years of his life, his intelligence work had now killed his only children. Abdul Al Salam’s younger brother, Nabil, asks if detainees are human beings in the eyes of the US Government? He says that he had hope when President Obama was elected: he lost it very fast when he saw that Guantanamo’s announced closing was quickly forgotten about. Scores of journalists have interviewed him and his family for the past few years. Nabil still believes that those interviews can make a difference. Conversely, many Guantanamo families now refuse to meet journalists, since they believe that none of their testimonies amount to anything but boosting the profiles of the Westerners who “make it” to Yemen. High profile US lawyer David Remes took Abdul Al Salam’s case in 2005. He visited Sana’a on six occasions, and so far, there has been no progress. Abdul Al Salam is frustrated by what he calls Remes’ poor performance. He is even wondering if Remes is not a US spy. He wants to be represented by a new lawyer. As our meeting comes to an end, I ask both brothers if they believe that the new Yemeni government will stand up to the US regarding Guantanamo and other issues. I explain that many in the West believe that Yemen is now on the democratic path as a result of the so-called Arab Spring. Nabil replies: “it is like we are in a bigger prison than that of my brother, only ours is a little nicer.” According to him, only one entity can save his brother: God. Et vous pensiez que la « Guerre Contre la Terreur » était finie ? Pas pour François Hollande…2/2/2013 Par Victoria Fontan et Adolphe Kilomba Traduit de l'anglais par Mait Foulkes On dit que l’on n’a rien sans rien… Un Etat peut-il vraiment se poser en sauveur désintéressé de l’une de ses anciennes colonies ? La France a lancé l’Opération Serval au Mali le 11 janvier 2013, officiellement pour repousser « un assaut par des éléments terroristes venant du nord, dont la brutalité et le fanatisme sont connus dans le monde entier».(1) Il est vrai que le nord du Mali était la dernière victime en date d’un régime similaire à celui des Talibans, qui terrorisait les populations qui y étaient soumises. L’amputation publique de voleurs présumés ainsi que des lapidations ont eu lieu dans la ville de Gao pour faire respecter la charia.(2) L’héritage culturel et architectural de Tombouctou a été détruit.(3) Les femmes ont été contraintes de porter le hijab musulman, les populations locales se sont vues soumises à un couvre-feu, et une police islamique veillait au respect de ces mesures. Bref, l’idée que n’importe quel Occidental se ferait de l’enfer sur terre. Pour des chercheurs en Paix et Conflits, c’est un rappel alarmant de la situation en Afghanistan avant 2001. Souvenons-nous : combien d’intellectuels français pensaient alors que la « Guerre Contre la Terreur » de Bush était une erreur grave, que sa rhétorique était ridicule, voire grotesque. Son discours, « Enfumons-les pour les faire sortir de leurs terriers », nous paraissait être celui d’un abruti texan, parvenu on ne sait comment à la Maison Blanche. Avance rapide : quelques années plus tard, ce cher président François Hollande répète exactement le même message à son auditoire captivé. Il dit qu’il veut « éradiquer le terrorisme » (4): tant mieux pour lui ! Les mentions de terrorisme, d’extrémisme et d’islamisme se sont multipliées dans les médias français ces derniers mois, culminant en une intervention qui est supposée « sauver les Africains d’eux-mêmes »… Comment rendre cela plus acceptable pour l‘opinion publique française, quelques semaines à peine après le rapatriement des troupes françaises du bourbier afghan ? Essayons de « sauver » un otage français, Denis Allex, des griffes diaboliques d’ « islamistes » somaliens, quelques jours avant le lancement de l’Opération Serval. Cela montrera aux Français de façon indiscutable à quel point ces « islamistes » sont nuisibles. Peu importe que l’agent de la DGSE soit sacrifié sur l’autel de la propagande d’Etat au cours d’une intervention en dernier recours ; lui et sa famille devaient bien s’y attendre quand ils signèrent au bas du contrat des années auparavant ! La situation au Mali depuis le début de 2012 est l’un des sujets brûlants qui ont retenu l’attention de la communauté internationale. Après deux décennies de stabilité politique et la tenue de plusieurs élections démocratiques, le Mali, à l’instar de plusieurs autres Etats africains, demeure faible, avec un appareil d’Etat impuissant. Plus de 50 ans après leur indépendance, les Etats africains font toujours face aux mêmes problèmes que dans les années 1960. Ils ne sont pas encore parvenus à s’affranchir de leur ancien pouvoir colonial.(5) Chaque Etat demeure sous le diktat de sa métropole occidentale. Ce système honteux continue à guider la politique du Conseil de Sécurité de L’ONU quand il examine les questions relatives à la paix et la sécurité dans la région. Le feu vert de l’ancienne métropole fait toujours partie intégrante du mécanisme de prise de décision. Par conséquent, le Conseil de Sécurité de L’ONU n’adopte jamais de résolution concernant un Etat africain sans prêter l’oreille au préalable à l’avis de son protecteur colonial. On peu en citer plusieurs exemples depuis les années 1990 : en Afrique francophone, l’implication de la France dans le génocide rwandais de 1994 ; la réforme agraire qui plaça le Zimbabwe sous le coup de sanctions économiques internationales initiées par le Royaume-Uni ; le bras de fer en Côte d’Ivoire avec la France tirant les ficelles au Conseil de Sécurité de L’ONU ; l’intervention française au Mali, etc. Ces quelques exemples prouvent à quel point la route vers la décolonisation reste longue et tortueuse. Concentrons-nous sur l’intervention française au Mali. Le conflit qui oppose le nord du Mali, peuplé de nomades, au reste du pays depuis les années 1990 s’est exacerbé en mars 2012, juste après la chute du régime de Kadhafi en Libye. Depuis lors, l’armée malienne a été incapable de faire face à l’insurrection et toujours mise en déroute par les « jihadistes ».(6) Après dix mois de conflit et de médiations stériles menées conjointement par l’ONU et la CEDEAO, sous la présidence du Burkina Faso, la situation s’est aggravée depuis le début de janvier 2013. Le cessez-le-feu de facto entre le gouvernement malien et les différents mouvements islamiques représentés par le Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) s’est effrité suite à la dernière attaque d’un groupe dissident, Ansar Dine, qui a tenté de saisir Konna et Mopti dans le sud, sur la route de Bamako. En reprenant le contrôle de ces villes du sud, le président malien a officiellement invité la France à intervenir pour protéger la république malienne en danger. Le gouvernement français a aussitôt déployé des troupes pour confronter Ansar Dine. La France s’est plus investie qu’aucun autre pays de la communauté internationale, montant en première ligne et dirigeant l’intervention, comme cela avait été le cas en Libye. Quel que soit le commentateur à qui l’on se fie, l’intervention française au Mali a ravivé une myriade de questions. Cette intervention a également été interprétée de plusieurs façons sur la scène internationale. Certains intellectuels et écrivains considèrent qu’elle marque un retour à ce qu’il est d’usage d’appeler Françafrique.(7) En revanche, un autre courant de pensée estime qu’il s’agit de la seule façon de s’attaquer efficacement au bourbier local en vue de préserver l’intégrité de l’Etat malien. Si seulement la France revenait à cette bonne vieille Françafrique. Si seulement les forces affrontées étaient les mêmes qu’autrefois, faciles à corrompre, à vaincre et à récompenser politiquement. Mais la France ne réalise pas qu’elle joue dans la cour des grands, ceux de la « Guerre Contre la Terreur »… Revenons quelques années en arrière, et transposons le conflit en Afghanistan ; que voyons-nous ? Nous voyons des forces religieuses, autrefois soutenues et armées par un pouvoir occidental, qui prennent le contrôle d’un pays et imposent une interprétation de la charia à une population terrorisée. Nous voyons une intervention étrangère pour « libérer » cette population, qui dans le cas du Mali, n’est même pas générée par un attentat similaire à celui du 11 Septembre 2001, mais qui entraîne cependant la précipitation d’un acte de terrorisme --certes préparé de longue date-- quelques jours plus tard, dans l’Algérie voisine, contre l’usine de gaz d’In Amenas. Nous pouvons ensuite prédire un enlisement impliquant des combats de type guérilla, avec les alliés locaux du pouvoir occidental commettant des crimes de guerre, etc. Nous visualisons aussi un possible débordement dans les pays voisins, une radicalisation accrue des islamistes à travers le monde, l’usage de drones, et la terreur d’Etat. Tiré par les cheveux ? Ce scénario a été joué et rejoué ces dernières dizaines d’années, au point que les champions du monde du terrorisme d’Etat, les Etats-Unis d’Amérique, ne sont même pas tentés, cette fois, d’y participer… Pour n’importe quel stratège sain d’esprit, cela devrait tirer une sonnette d’alarme – mais pas pour le gouvernement français, qui a encore plus de culot que ceux qui s’intitulent eux-mêmes « le superpouvoir du monde». Il est vrai que l’AFRICOM, la nouvelle force néocoloniale des Etats Unis en Afrique, avait entrainé de nombreux chefs Islamistes contre lesquels la France se bat en ce moment… Souvenons-nous qu’il y a un an à peine, la brillante stratégie française au Mali consistait à procurer à certains nomades les moyens de combattre des groupes proches d’al-Qaida. Souvenons-nous aussi qu’une fraction de ces nomades faisaient partie de l’armée de Kadhafi, alors que d’autres étaient sympathisants de l’insurrection libyenne dont plusieurs membres, tels que le gouverneur de Benghazi Abdelhakim Belhaj, était eux-mêmes proches d’Al-Qaida.(8) Jetons dans la balance une grande quantité d’armes soudain disponibles (suite à la chute du régime de Kadhafi, qui exerçait autrefois un contrôle très strict), les liens du sang et ceux du clan : rares sont ceux qui vont choisir de se battre contre leurs cousins pour défendre les intérêts de leur ancien maître colonial – cela paraît évident. Remémorons-nous aussi quelques notions très basiques d’étude des insurrections, dont n’importe quel officier a connaissance. Quand l’insurrection commence à s’organiser et lance ses premières actions militaires, elle va commettre des actes de terrorisme pour susciter une réaction du gouvernement, le plus souvent aux dépens de la population locale, prise entre deux feux.(9) Les actes de terrorisme commis par les « ennemis » de la France au Mali visaient les institutions de l’Etat malien, ainsi que les intérêts étrangers dans la région – dans ce cas précis, en Algérie. Le régime algérien est l’un de ceux qui ont réprimé l’islamisme de la façon la plus sanglante, au prix de milliers de morts parmi la population civile. Obtenir que les Français s’associent à ce régime sanguinaire en réponse à la crise des otages d’In Amenas a été un trait de génie de la part d’Al-Qaida au Maghreb Islamique (AQMI). Cela ne va faire que renforcer leur emprise sur la région, de même qu’au Mali.(10) En outre, les troupes de l’armée malienne, également alliées des Français, ont commencé à perpétrer des crimes de guerre…(11) Est-il jamais venu à l’esprit du président Hollande qu’en plus de « guerres justes », nous devrions aussi avoir des guerres propres? Il n’est guère surprenant que dans le cas d’une « guerre juste », les experts en droit se contentent d’analyser le cadre légal d’une telle intervention. Le courant juridique dominant considère, à juste titre, l’intervention française au Mali comme légale au regard du droit international, en raison de la résolution du Conseil de Sécurité de l’ONU autorisant le déploiement d’une force internationale pour porter assistance à l’Etat malien. L’intervention française au Mali base aussi sa légalité sur le fait que le président malien a invité officiellement le gouvernement français à intervenir militairement sur son territoire. D’autres experts en droit international la fonderaient sur la responsabilité de protéger. Nous savons tous comment cela s’est terminé en Libye, maintenant qu’avec un recul de quelques mois, nous en sommes à peser les conséquences de la campagne pour « libérer » ce pays. Pourquoi la France est-elle aujourd’hui au Mali ? Ne cherchons pas plus loin que les intérêts économiques dans la région, particulièrement l’exploitation de l’uranium au Niger, ainsi que la lutte d’influence entre la France et les Etats-Unis depuis le lancement d’AFRICOM. Plus de deux semaines après le début de l’opération, la situation paraît s'éclaircir: les Forces spéciales françaises protègent désormais les mines d’Areva au Niger, tout comme les troupes américaines avaient « protégé » le ministère irakien du Pétrole pendant le pillage de Bagdad en avril 2003… Le pays est différent mais la bêtise est la même : l’histoire se répète à presque dix ans d’intervalle, bien que les pacifistes libéraux au grand cœur s’y intéressent beaucoup moins, puisqu’après tout, il ne s’agit que de l’ « Afrique »... Pendant ce temps, et en préparation a un réveil brutal dès que la France aura a se frotter aux Islamistes dans les montagnes du nord Mali, les médias continuent à rallier l’opinion publique française a grand coups de manuscrits anciens brûlés a Tombouctou, dont tout de même 90% avaient été rapatriés a Bamako avant le début de la guerre, et une partie du reste officiellement « brûle » doit déjà se trouver en route vers des collectionneurs prives de New York, Paris ou Tel Aviv…, et de femmes ôtant leurs voiles Islamiques en signe de liberté retrouvée… De qui se moque-t-on à part des Maliens infantilisés ? Des Français aussi bien entendu, car en temps de crise, la facture de l’Opération Serval ne sera pas des moindres pour les finances publiques. Pour reprendre les sages propos du professeur Michel Galy, la Guerre Contre la Terreur de Hollande se déroulant au Mali est, en fait, partie intégrante d’une « Guerre à l’Afrique » entreprise de très longue date.(12) Elle va traîner en longueur, et elle aura des conséquences dévastatrices pour la région et sa population. Nous aurions pourtant bien tort nous faire du souci ; cela va nous donner, à nous les travailleurs de l’industrie de la paix, des gens à sauver pour de nombreuses années – comme cela a été le cas dans ce bon vieil Afghanistan. Notes: 1 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-20991719, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 2 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-19155616, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 3 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/01/opinion/the-end-times-for-timbuktu.html, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 4 http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/monde/20121009.FAP0010/hollande-une-intervention-au-mali-pour-eradiquer-le-terrorisme-dans-l-interet-du-monde.html, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 5 Gerald Caplan, L’Afrique Trahie, Actes Sud Junior, Arles, 2009. 6 Jihadistes: C’est le nom que se donnent les membres du MUJAO, d’AQMI et d’Ansar Dine. Ils disent que la guerre qu’ils mènent est une guerre sainte. 7 Françafrique: Ce nom explique la relation trouble et difficile à comprendre entre la France et ses anciennes colonies. Ce concept a été popularisé par Jacques Foccart, autrefois le principal conseiller de Charles De Gaulle. Il a également été conseiller de François Mitterrand. Pour plus de détails au sujet de ce mot « magique » inventé par l’ancien président ivoirien Félix Houphouet-Boigny, voir Patrick Pesnot, Les Dessous de la Françafrique (Nouveau Monde Poche, Paris, 2011). 8 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14786753, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 9 Roger Trinquier, La guerre moderne (Economica, Paris, 2008). 10 http://www.france24.com/en/20130120-algeria-hostage-crisis-death-toll-expected-rise, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 11http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2013/01/25/nouveau-temoignage-sur-des-executions-sommaires-au-mali_1822443_3212.html, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. 12 http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2012/06/20/l-intervention-militaire-au-mali-n-est-pas-une-solution_1721307_3232.html, consulté le 25 janvier 2013. Cet article a été publie dans 6 pays, mais curieusement pas en France... on se demande pourquoi... :-)

1er février 2012 Le Dr Victoria Fontan réfléchit au rôle joué par l’honneur et l’humiliation dans la motivation des insurgés tant en Irak qu’en Afghanistan – et en particulier dans le cas du soldat afghan qui a récemment abattu quatre soldats français participant à la mission de l’OTAN dans ce pays. Traduit de l'anglais par Mait Foulkes Rechercher tous les aspects de la guerre en Irak et son bilan humain, tant du côté irakien que du côté de la coalition, ne m’a jamais posé de problème. Je portais d’ailleurs un jugement catégorique sur certains de mes collègues américains qui négligeaient d’évaluer de façon critique les raisons de la formation de l’insurrection irakienne. Ayant passé beaucoup de temps à vivre et à discuter avec des Irakiens, il me paraissait évident qu’un sentiment d’humiliation collective pouvait expliquer des actes de résistance individuels ou collectifs contre un occupant. Bon nombre des personnes que j’ai interviewées, d’un kamikaze sur liste d’attente à un ancien cadre d’Al-Qaida, établirent un lien direct entre la perception que leur honneur avait été souillé, et le besoin de le blanchir en perpétrant un acte de violence contre le symbole de cette humiliation – en l’occurrence, n’importe quel membre ou sympathisant des forces de la coalition. En Irak, l’honneur est une caractéristique essentielle de l’identité individuelle et collective. Il tempère les relations à tous les niveaux de la vie quotidienne et dans toutes les sphères de la société irakienne, depuis le secours que l’on doit prêter aux indigents jusqu’à la nécessité de maintenir intacte la pureté d’une femme. L’honneur engendre des qualités qui s’infiltrent dans la formation des valeurs, les comportements et les actions, et il est étroitement associé à la spiritualité : de même, on considère que la tradition de la chevalerie assurait la cohésion du tissu social en Europe avant la création des États modernes. En Irak, des traditions séculaires liées à l’honneur coexistent avec un système moderne d’ordre public. Cependant elles supplantent toujours ce dernier quand ils entrent en conflit - autrement dit, dans le cas d’une humiliation ressentie. La honte forme le revers du système irakien basé sur l’honneur. Avishai Margalit qualifiait l’Irak de « société de la honte », signifiant ainsi que toute manifestation publique de honte doit être compensée pour que l’individu regagne son honneur/identité. Faute de quoi cette honte pourra entacher une famille et un clan pour des générations. En Irak, la “mort sociale” est pire que la mort. Par conséquent, l’absence de négociations pour réparer une atteinte à l’honneur d’un individu va générer une escalade de la violence en représailles. Je l’ai observé de mes propres yeux à Fallujah au printemps 2003 : chaque homme tombé sous le feu américain, et l’humiliation en résultant, ont entraîné des représailles inéluctables de la part de sa famille, aboutissant à la destruction partielle de la ville au printemps 2004. Un autre triste exemple date également du printemps 2004, quand la première vidéo de décapitation fut rendue publique : l’Américain Nicolas Berg, juste avant d’être abattu comme un mouton, y citait le scandale des photos d’Abu Ghraib comme étant la raison principale de son exécution imminente. Pourtant à l’époque, le débat public aux Etats-Unis ne fit pratiquement aucun rapprochement entre le sentiment d’humiliation collective ressenti par la population et le développement de la violence politique, à travers notamment d’actes terroristes. On souligna abondamment la brutalité de l’acte, en passant sous silence sa nature symbolique ou sa signification culturelle. Le Human Terrain System en Afghanistan fut créé pour aborder certains de ces problèmes culturels, cruellement négligés en Irak. Cette initiative prévoyait notamment de déployer sur le terrain des universitaires dans le but d’améliorer les relations entre l’occupant américain et les Afghans, étant donné que les différents peuples d’Afghanistan observent un système similaire, basé sur l’honneur. Tout en pensant cela pourrait contribuer à sauver des vies humaines au coup par coup, je vis d’un œil critique cette exploitation flagrante de connaissances académiques pour valider une occupation. Les recherches déjà effectuées sur l’honneur et l’humiliation seraient-elles uniquement destinées à servir de manuel de bonnes pratiques pour les forces d’occupation ? Tout ce travail académique et “rationnel” ne m’avait pas préparée à apprécier à quel point il serait difficile d’utiliser les mêmes recherches avec ma propre armée en Afghanistan. En tant qu’ancienne élève du Prytanée Militaire de la Fleche, d’anciens camarades m’ont inscrite à plusieurs groupes de soutien sur Facebook, établis pour soutenir le moral de nos camarades de promotion déployés en Afghanistan. J’étais témoin, virtuellement, de l’angoisse quotidienne de leurs proches, de leurs difficulté à faire face à un nombre croissant de mauvaises nouvelles, de leur incapacité à comprendre pourquoi ils étaient pris pour cible par les Afghans. A chaque nouveau meurtre, je trouvais difficile de ne pas dénoncer le lien entre occupation, humiliation et violence politique, de ne pas expliquer qu’il y avait une raison derrière les épreuves qu’eux-mêmes et leur proches enduraient, que les Afghans n’étaient pas simplement des ennemis de la liberté, sauvages, violents et ingrats. Mais je redoutais de contrarier mes camarades, de porter atteinte à notre longue amitié, et aussi de gêner ma sœur qui est dans l’armée. Comment aurais-je pu me permettre de “philosopher” alors que nos camarades étaient convaincus de remplir leur mission ? A chaque nouveau décès je sympathisais avec mon groupe, j’offrais mon soutien, je partageais le deuil. Désormais, je ne peux plus le faire. Le 20 janvier dernier, durant un entraînement sportif, un soldat afghan a ouvert le feu sur ses compagnons français, en tuant quatre et en blessant de nombreux autres. Le Ministère de la Défense français a affirmé que ces soldats faisaient partie d’une équipe de liaison et de mentorat opérationnel (ELMO) ayant pour rôle de renforcer l’armée afghane. [i] Les médias français s’en sont largement fait l’écho. [ii] Le Ministre de la Défense Gérard Longuet a aussi prétendu que l’homme qui a abattu les soldats français était en fait un Taliban infiltré dans l’armée afghane. [iii] Certains rapports sont allés jusqu’à insinuer que ce n’était même pas un soldat mais simplement “un individu portant un uniforme de l’armée afghane”. La première de ces affirmations est trompeuse, quant à l’autre elle est complètement erronée. La présence française en Afghanistan n’a pas simplement pour but de former l’armée afghane. Elle implique toute une logistique, une présence sur le terrain et des opérations spéciales menées de pair avec les autres membres de la coalition. Ce qui signifie des opérations où une population prise entre deux feux, entre les insurgés talibans et les soldats de la coalition, peut facilement percevoir les étrangers comme des “occupants” malintentionnés. Quant à l’assassin, ce n’était pas un Taliban : c’était un soldat afghan. Quand on l’interrogea sur les motivations de son geste, il affirma avoir réagi à la vidéo des marines américains urinant sur les cadavres d’Afghans rendue publique quelques jours auparavant. [iv] La guerre et l’occupation ne sont jamais des entreprises philanthropiques et bénignes. Elles génèrent des ennemis, elles entraînent des représailles, elles tuent bien plus qu’elles ne soulagent. Aucun “système humain sur le terrain” ne peut coexister innocemment avec des mesures brutales de contre-insurrection. La vidéo mise en cause montre que c’est le système d’occupation lui-même qui est responsable de ces images, qui autorise quelques fortes têtes à profaner les corps de leurs ennemis morts. Pourquoi est-il si difficile de comprendre que la violence ne peut apporter la démocratie, la paix et la coexistence? Pourquoi les médias français ne s’interrogent-ils pas sur les motivations qui ont poussé un soldat à ouvrir le feu sur ses camarades ? Ce soldat est aussi réel que les quelques “pommes pourries” qui ont pris tout le blâme pour la maltraitance infligée à Abu Ghraib. Ce n’était pas un “Taliban” enragé, simplement un individu qui cherchait à laver l’honneur collectif qui venait d’être souillé, qui tentait de réparer l’irréparable. J’ai adressé un article consacré aux motivations et à l’identité de ce soldat afghan au groupe Facebook dont je fais partie avec mes anciens camarades de l’armée. A ce jour, je n’ai été gratifiée d’aucune réponse, d’aucun accusé de réception, en bref, d’aucun signe de vie. Les Français surnomment leur armée “la grande muette”… Le raisonnement analogue que j’avais tenu au sujet de la guerre en Irak, du temps où les insurgés étaient encore qualifiés de “terroristes” dans la presse américaine, avait provoqué des réactions violentes outre-Atlantique : un débat parmi d’autres qui ouvrit la voie à un changement de la perception populaire des insurgés irakiens. En matière de résolution de conflit, nous avons l’habitude de dire que toute forme de communication, positive ou négative, vaut mieux que ce que nous qualifions d’“hostilité autistique” : quand les protagonistes d’un conflit refusent mutuellement de reconnaître la présence de l‘autre. Aux Etats-Unis j’ai été vilipendée, j’ai reçu des menaces de mort, et j’ai même été invitée à participer a la tristement célèbre émission « O’Reilly Factor » sur la chaine Fox News. En France, mes questions n’ont rien provoqué du tout. Mon raisonnement est invisible. A mes camarades et à ma famille, je voudrais dire qu’à moins de questionner et de comprendre les motifs qui ont pu conduire un soldat afghan à ouvrir le feu sur ses compagnons d’armes, nous continuerons à récupérer nos proches dans des cercueils plombés. La présence de la France en Afghanistan ne vaut pas les morts qu’elle provoque, les vies anéanties, les familles brisées. La France n’a pas de mission valide en Afghanistan. Les Afghans vivent sous occupation étrangère depuis plus de trente ans. Pendant tout ce temps, leur système basé sur l’honneur n’a pas changé, et il n’est pas prêt de changer. La “démocratie”, les réformes, la “bonne gouvernance” mises en place grâce aux mesures coercitives de l’occupant, le bras de la paix libérale, tout cela n’effacera jamais la place prépondérante occupée par l’honneur en Afghanistan, comme dans toute autre “société de la honte”. Verser des larmes de crocodile à chaque décès n’aide en rien à soutenir nos camarades. Soutenir nos troupes, cela veut dire faire pression sur notre président pour qu’elles reviennent en vie d’une mission que la majorité des Afghans ne cautionne pas. Le président Sarkozy ferait n’importe quoi pour être réélu, il serait peut-être même prêt à écouter une opinion publique forte, critique et indépendante. Quant à moi, je cours maintenant le risque d’être “bannie” de mon groupe Facebook. [i] http://www.defense.gouv.fr/operations/afghanistan/actualites/afghanistan-4-militaires-francais-tues-par-un-soldat-afghan [ii] http://www.estrepublicain.fr/actualite/2012/01/21/gerard-longuet-ce-matin-a-kaboul-la-mission-reste-la-meme [iii] http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/monde/20120121.OBS9427/afghanistan-les-francais-abattus-par-un-taliban-infiltre.html [iv] http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/video/2012/jan/12/video-us-troops-urinating-taliban; http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/afghanistan/9030919/Afghan-soldier-killed-French-troops-over-US-abuse-video.html |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed