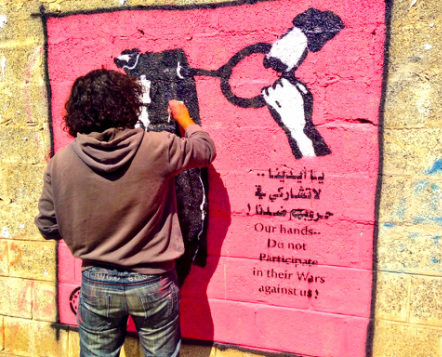

Murad Subay, 7th Hour, Twelve Hour Campaign, Sana'a Murad Subay, 7th Hour, Twelve Hour Campaign, Sana'a He is painting graffiti on a wall opposite a westernized shopping mall. All major media networks are there, Reuters, Al-Arabiya, Agence France Presse, they try to capture his attention as they are buzzing around him: “Murad, here please,” “Murad, Murad!,” “Hello Murad, can you explain what you doing;” a fixer approaches him as he tries to concentrate: “Murad, my client would like a bit of time to interview you later, can you make it?”… If twenty-seven year-old Murad Subay is a star, he does not behave like one. He does not see the circus going on around him as a disturbance, he embraces it and makes it part of his work. A self-made artist, he is painting to raise awareness on certain issues, and he channels the attention from his own person to the message he is trying to spread, both locally and globally. It is clear, vivid, uncompromising: two hands hold a hand-grenade circular safety pin, ready to undo it, a sentence is written both in Arabic and English “Our hands… Do not participate in their wars against us.” It all started in 2011, after the civil war that opposed dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh and other tribes, an offset of the “Arab Spring” which could well have transformed Yemen into another Syria. As opposed to Syria, the Yemeni dictatorship was backed by the US, and only a cosmetic change occurred: Saleh’s Prime Minister was elected in office with 99.6% of the vote.(1) Murad explains: “the city bore the scars of the clashes, so I went out and started to paint over them. After one week, people started to come and paint with me. Parents sent me their children, even soldiers put their weapons down and took brushes instead.” The Color the Walls of Your Street campaign was born. After to months, all major cities in Yemen took the initiative, colors appeared in Aden, Ta-az, Ebb, and Hodeidah. The campaign received international coverage, and was very well received by the Yemeni population. As Murad learned stencil art, his second campaign was planned. For some, it took a political turn, yet Murad stresses that it is not his aim: “we are not politicians and we don’t have power to stop what is happening to our country. The only thing we can do is making noise around important issues.” During seven months, every Thursday, faces of people “disappeared” by the government, some since the 1960s, were painted all over Sana’a and other towns. Next to the faces, the date of the disappearance, and the idea that no one can vanish from public view. Walls became a symbol of hope, of unity, not only for the disappeared but also their families, which were brought at the core of public spaces. The Walls Remember Their Faces campaign had a decisive impact. Maybe the US embassy asked that its puppet "ally" throw a bone to its people… Four months after the campaign started, Mutar Aleriani was released. He had been disappeared since 1981. He was tortured so badly with a drill that he can no longer move his legs. Confined to a wheelchair, he is not being looked after by his daughters. Murad met him in Hodeidah, his words against US ally Abdullah Saleh were understandably very harsh. Murad explains how the campaign has brought humanity onto the whole issue; meeting Mutar had a huge impact on him. Murad realizes that he cannot design a campaign for all the issues that Yemen is facing right now. He is not financed, and rejects all offers of help from international organizations, including the UN. He says that he needs to remain independent, so that the impact of his campaigns cannot be compromised: “the supplies could be coming from [not so benevolent neighbors] Saudi Arabia or Iran, we just cannot allow that.” Everyone who turns up brings their own supplies, and people who are part of the network also donate items randomly. Murad is his own complex adaptive system.(2) Paintings speak louder than academic lectures. Murad’s Twelve Hour campaign is now famous around the world for its coverage of the drones issue. A little boy writes right below a drone: “why did you kill my family.” This question is timely: many children in Yemen are asking themselves the question, day in, day out. Chances are that Westerner meeting them will be asked, just like I was.(3) Another painting by Hadel Almowafak represents a Tao symbol, on top the drone, and at the bottom a dove: the vivid imagery of Liberal Peace, the peace that kills innocents, the peace that I teach as pat of the UN. The drones representations figure in Murad’s Twelve Hours Campaign. Each hour of a clock brings in a new issue that Yemen is facing: weapons, sectarianism, kidnappings, poverty, and internal strife. Will one of the hours focus on Barack Obama’s war secret war against Yemen?(4) Murad’s stencils ought to reach the streets of Washington, D.C., New York and San Francisco, so that Yemenis would no longer be disappeared from the world’s view.(5) We often ask ourselves what we can in the face of injustice. Murad gives us a plain answer: noise. (1) See http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/25/world/middleeast/yemen-to-get-a-new-president-abed-rabu-mansour-hadi.html, accessed on January 20th 2014. (2) See Decolonizing Peace, chapter 3. (3) Please circulate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un0vxahkYFM (4) See http://dirtywars.org (5) For more information on Murad Subay and Hadel Almowafak, see: http://muradsubay.wordpress.com and http://hadeelalmowafak.wordpress.com

2 Comments

Abdul Rahman Ali Barman in HOOD's Office, Sana'a Abdul Rahman Ali Barman in HOOD's Office, Sana'a Abdul Rahman Ali Barman is a Yemeni lawyer dedicated to human rights. His organization, HOOD, is active since 1998, and has seen many cases over the years. In a dictatorship, the amount of threats that such an NGO receives from the government is always a testimony to its efficiency. In 2011, HOOD’s central office in central Sana’a received direct cannon rounds from a nearby army barrack: they must have been doing something right. They continued their work from a tent for over a year and a half, and are now back to their headquarters processing all sorts of human rights violations. Abdul Rahman says that since the removal of President Saleh and the subsequent landslide victory of his former deputy Abd Rabu Mansour Hadi, not too difficult to obtain since he was the only candidate, things are looking up in Yemen. There are improvements in some areas such as press and internet freedom, people are becoming more free to share their ideas, up to a certain point of course. There are still enforced disappearances and random arrests of journalists. Guilt by association prevails in Yemen, where the suspicion of any link with al-Qaeda can land someone in prison. There, the interrogation techniques have not changed. After all, democracy is a lengthy process, it requires time to hatch, or so we are told by Liberal Peace fairy tales. Detainees are still subjected to the same type torture as before the Arab Spring: electricity, suspension of arms twisted behind the back, punching, etc. Why is the human rights situation in Yemen so important, and what is the connection to drone strikes and targeted killings carried out by the US government on Yemeni soil? From an International Law perspective, there are two different frameworks that could apply, depending on whether the US has declared war against another Nation State. If it has, there are rules on how to conduct a war with a minimum damages, under the precepts of International Humanitarian law. If it has not, the use of lethal force is much more difficult to justify, and falls under the precepts of International Human Rights Law. From the perspective of the latter framework, the practice of targeted killings could be regarded as an extrajudicial execution. That’s however not counting with the help of the United Nations Charter. Under its article 51, a country can kill if is has an “invitation from the state where force is used to join with it in armed conflict hostilities.” (1) The US claims that the Yemeni government has asked its help against al-Qaeda, and that therefore Article 51 applies. Abdul Rahman strongly disagrees, and explains that there have been several debates in parliament about this: “how can a country which is not even a democracy ask for this help? The Parliament never requested anything, or passed any law regarding this supposed assistance. No one has access to any documents of the sort. Even the current Prime Minister declared on al-Jazeera never to have seen such documents.”(2) Article 51 cannot work for two reasons. First, the assertion that the current Yemeni leadership was “elected”, in a sad excuse for a democratic process, since there was only one candidate to vote for. Abdul Rahman argues that therefore is no legitimacy to be found in the current government. Second, there was no official request, validated by Parliament, for any military assistance from the US. From an International Human Rights Law perspective, the Obama administration is therefore carrying out extrajudicial executions. Who benefits from this War Crime? Certainly not only the usual suspect, i.e. the Yemeni government. Abdul Rahman mentioned the recent execution of two moderate al-Qaeda officials killed in drone strikes, Fadel Qasr and Mohammed el-Hamda. According to him, Qasr and el-Hamda were members of the AQAP council, the Shura, which decides on operations across the country. They both had withdrawn during the vote on several operations, which they did not agree with. Their names and locations were conveniently given to the Yemeni government to facilitate a purge within AQAP. According to Abdul Rahman, AQAP’s military leader, Qasm al-Raimi, is actually very close to the previous and current governments. Indirectly, the US government is therefore aiding and abating AQAP, assisting in its purge from the inside. Moderates have never made convenient enemies. Can NGO workers too become enemies of the US? Abdul Rahman does not discard the possibility. Last December, Abd al- Rahman Omair Al Naimi, a Qatari colleague from HOOD’s sister organization Alkarama, was designated as a supporter and financier of al-Qaeda by the US Treasury Department. It seems that working on drones and human rights in Yemen may land anyone, author included, in trouble. Abdul Rahman explains that when it comes to these issues, and the power that the US has on the government, these activists could even end up in prison. HOOD and AlKarama’s links with international NGOs such as US-based Code Pink have granted them protection both in Yemen and abroad to a certain extent. However, Abdul Rahman sees these organizations’ lavish spending on the back of their suffering with much caution. He explains: “if they invested even three percent of the funding they obtain thanks to our suffering to help us train Human Rights delegates on the ground, this would enhance our efficiency tremendously.” The Peace Industry as well as free-lance journalists revels on the drones “story,” any other international coming to Sana’a to work on the issue is likely be ignored by the “specialists.” The drones also created a certain gold rush. Alkarama designates the US extrajudicial killings as a second-generation Guantanamo. Abdul Rahman confirms this as many of the targets of US strikes are former prisoners. The most infamous of the attacks, on the town of Majella, fits this profile. On December 17th 2009, the US carried out a “double tap” on a small village nine hours of Sana’a. It killed up to forty-two people, most women and children. This “double tap” technique is notoriously used by al-Qaeda in Iraq or in Afghanistan. It consists of a first strike followed by a second attack a few minutes later, under the understanding that the people rushing to the scene to help others are guilty by association and therefore deserve to die too. In Majella, the first strike consisted of four Hellfire missiles, followed a few moments later by a Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (BGM-109D) “designed to carry 166 cluster bombs, each containing approximately 200 iron splinters that can reach a distance of 150 [meters] from the drop point.”(3) The target of the attack was Mohammed al-Qazimi, a former alleged al-Qaeda associate who had spent fie years in a Yemeni jail, and had been released shortly before the strike. Since he had returned to Majella, he passed an army checkpoint morning and afternoon to go and buy his daily bread and khat.(4) He could easily have been arrested and tried at any time. What therefore justified the strike, and the lavish spending of US taxpayer funds to kill someone who was completely accessible to Yemeni law enforcement? Given the price of the ammunition used, the attack cost a minimum of two million US Dollars, a sum that could easily have been invested in the development of the village, hence fostering pro-US sentiment among the population. After the Majella attack, President Saleh rang the mayor to justify the killing, arguing that all involved, including the women and children, had ties to al-Qaeda. The mayor allegedly responded: “I hoped that when they had died, the children would have known how to read and write; I hoped that when they had died, their stomachs had been full; I hoped that when they had died, they would have had electricity, computers and access to internet.” The attack whose funds could have been put to good use boosted AQAP support in the region. Abdul Rahman recalls the funeral of Majella victims with emotion, especially this old lady who pleaded, referring to the US: “they even have laws that protect animals, why can’t they just consider us like their animals?” (1) See http://law.wustl.edu/harris/documents/OConnellFullRemarksNov23.pdf, p.1. (2) Interview with Abdul Rahman Ali Barman, January 9th 2014, Sana’a, Yemen. (3) See http://en.alkarama.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1157:yemen-license-to-kill&catid=66&Itemid=215, p. 66 (4) The khat is a local leaf that is chewed daily for its stimulant properties.  Anti-drone mural by Hodey Al-Mowafak, Sana'a Anti-drone mural by Hodey Al-Mowafak, Sana'a Farea al-Muslimi sees himself as a friend of the United Sates. Born and raised in Wessab, a village nine hours of Sana’a, and one of twelve living siblings, he was destined to be a farmer. When he was in 9th grade, he obtained his first State Department scholarship to study English, and soon ended up in California as part of the Youth and Exchange Study program, geared towards strengthening friendship between the US and Muslim countries. All went according to plan, Farea soon rose to the top of his class, he visited lots of churches, attended countless barbecues and, cherry on the cake, found a second father in a US Air Force service member. Farea’s State Department-engineered American Dream could not have become more complete. He returned to the Middle East to be awarded yet another scholarship at the American University of Beirut. He was programmed to be one of those countless “local” ambassadors that roam around peace, development or human rights conferences, making excuse upon excuse for the war crimes of Western powers, the North-South divide, or the unequal power dynamics between their neo-colonial masters and the subaltern rest. Malcolm X could have seen Farea as a picture-perfect house-Muslim, catching a cold whenever his master would sneeze. Not quite… Farea’s own village was targeted by a strike on April 17th 2013. On that day, four people were killed. The target was Al-Hadidi al-Radami, a social worker suspected of having ties with Al Qaeda in the Arabic Peninsula (AQAP). As the village mediator, he was actually very close to local authorities. He had returned to the village in 2011 after being imprisoned for fighting against the US in Iraq. Since his return, some political opponents of the Saleh regime both in Wessab and Sana’a to enquired to the police about him, only to be told that he was a reformed character, a pillar of the community. According to them, he had paid his debt to society and deserved to live a peaceful life. This did not prevent him from being put on a target list. According to villagers, Wessab had been observed by drones for well over a year. Farea tried to make sense of the attack. Why wouldn’t the suspect be arrested, interrogated, and tried? Why did local people have to die with him? Why would his village be subjected to the terror of a drone attack? What would warrant such a targeted killing? According to the National Defense Authorization Act of 31 December 2011, one does not need to be part of any group to be the victim of targeted killings: guilt by association, under the clinical term ‘associated forces’ is enough. Farea explains that there are four types of targeted killings, the first two including drones only. Under Type One, President Obama provided four clear conditions for a killing to take place: the person has to be designated as a person of interest under US law; he or she must represent a direct threat to the US; the target cannot be captured; and, finally, the operation must not target civilians. The attack on Wessab clearly does not meet any of those criteria. It was carried out nonetheless. Type Two, which could well have applied, is the “signature strike”, whereby any high ranking military officer as well as President Obama can order the death of a anyone displaying suspicious behavior. Now there is a problem right there: “what is suspicious behavior in the US is completely normal behavior here,” explains Farea, “[it] can represent every single Yemeni in Yemen: if I am with you, going to a wedding outside Sana’a, we will obviously be between the age of 15 and 65, we will be carrying guns [they are part of the Yemeni dress code], and we will be a group, [that’s] enough! It is not even intelligent criteria anymore.” Farea calls this state terrorism, and he is afraid that it is going to get worse. He testified before the US Congress Judiciary Committee six days after the attack on Wessab, and so far, nothing has changed. He says that the logic behind the strikes is devoid of common sense, and that it actually encourages more support for AQAP on the ground. Since the US is becoming its enemy, and terrorizing the population while its puppet government does not react, it cannot end well for any party involved. At present, AQAP is actually much more politically savvy than the US, it has paid compensation to the owner of a house destroyed by a drone strike. Since the US nor the Yemeni government compensate civilians after strikes, this can win many hearts and minds. Farea was educated in the US. He can put himself in anyone’s shoes, and right now, he is a bridge between increasingly estranged nations. He says that the strikes have changed fabric of his own society: ‘if a mother wants to scare her child into going to bed, she used to say that she would call a dad, now she says that she will call the drones.” If at all possible, it will undoubtedly take more than a couple of scholarships to reclaim the hearts and minds of those children’ generation.  Mohammed al-Qawli showing his brother's car Mohammed al-Qawli showing his brother's car Mohammed al-Qawli, a former Headmaster in his late forties, has been restless for nearly a year. On January 23rd 2013, his brother, schoolteacher Ali Ali al-Qawli, was killed in a drone strike, alongside seven other men. They were traveling to the north of the village of Qawlan, half an hour from the Yemeni capital Sana’a, when four hellfire missiles hit their Toyota Hilux. Mohammed remembers hearing an explosion: he went out to see if the Hilux was still in the village, and that’s when he realized that something bad might have happened. He knew about drone strikes but discarded the possibility. The Americans had never targeted his area, notoriously close to the previous government elite. He and other village members travelled to the scene of the explosion: nothing could have prepared them for what they were about to see. The scene was on fire, filled with charred human remains and debris. The car had been moved 10 meters away from the impact of one of the missiles, close to a house on the other side of the road. Water was gushing from an irrigation tube, and men from a nearby village were walking aghast among the debris. Mohammed was on autopilot. Villagers pointed to a charred body at the back of the car, whose teeth were unmistakably those of his brother. Soon, security services turned up. All the officials cared about was to find the car’s number plates. They soon departed the scene. Afterwards, onlookers gathered all the remains they could find: more than one hundred. They were immediately taken to Sana’a for a forensic examination. Immediately after the strike, the Yemeni government declared that al-Qaeda operatives had been killed in the attack. This generated a massive protest from the local tribes, the government was forced to issue a retraction: Ali al-Qawli and all other occupants of the car were declared innocent of any crimes. Since Ali was a quiet schoolteacher with no links to any political organization, Mohammed started asking himself who else in the car could have been targeted. That’s when it dawned on him: a known opponent of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh was in the car, Rabieh Hamud Labieh. Labieh, a democratically elected local councilor, had turned against Saleh during the 2011 Arab Spring-related demonstrations. He was notorious for having denounced the smuggling of government weapons between Sana’a and Saleh’s fief, right after his demise. He had been an opponent to the new regime, arguing that th country was still a dictatorship. According to the Yemeni National Organization or Defending Rights and Freedoms (HOOD), the Yemeni government has been instrumental in assisting the US government with its strikes, from the collection of incriminating “evidence” to the collection human intelligence. In sum, the Yemeni government says who to strike, where and when. For Mohammed, it makes no doubt that the government used the US to get rid of its political opponent, a view shared by HOOD and Swiss-based NGO Alkarama. Not only is the “war on terror” not nearly over, but also one can conclude that the Arab Spring never really took off in Yemen, where Saleh’s successor, former vice-president Abd Rabu Mansour Hadi, continues to purge his political opponents. How much does it cost, in Yemen, to dispose of a democratically elected politician? One only needs powerful allies. Alkarama asserts that it would have been very easy to arrest Labieh and try him for treason. After all, there was a military police checkpoint only five hundred meters from the scene of the explosion. Four Hellfire missiles were launched at Labieh’s vehicle, preceded by more than a day of drone reconnaissance. Provided that the basic cost of a Hellfire is $65,000, counting the drone flying hours and personnel costs, the attack could have reached a $400,000 price tag for the US taxpayer. Since the Yemeni government cleared all occupants of any relationship with al-Qaeda after their death, this particular incident is proving to be a costly mistake. No compensation was offered to the families of the victims. Salim, the car’s driver, left behind an impoverished extended family. Ali left three ophans who are now being raised by Mohammed. Ali’s eldest, Mohammed Ali, asked me to film him as soon as I arrived in his house. He asks a very simple question to President Obama: “Sir, why did you kill my dad?” (1) As we parted, Mohammed says that he will never let go until he obtains an apology from the US government, and compensation for all its Yemeni victims. Whenever there is an attack elsewhere in the country, he races to the scene in own SUV, bought specifically for this reason. He then collects the remaining parts of the missiles and brings them to Sana’a. He has been documenting every strike since his brother’s death, and wows to do so until a missile strikes him eventually. Showing me part of a Hellfire that killed his brother, he defiantly claims: “this is the humanitarian aid we in Yemen get from the US, it is all one big lie, and I will never give up for all the victims’ sake.” (1) See the link to Mohammed Ali al-Qawli's question to President Obama: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un0vxahkYFM  Abdul Al Salam's younger brother Nabil Abdul Al Salam's younger brother Nabil Here is a cautionary tale for anyone out there working in intelligence, whether as a mere asset or a field operative. When your government is trying to get rid of you, what better cover but to accuse you of having links with al-Qaeda? One certainly can assert that Abdul Al Salam al Hilal had "ties" with al-Qaeda. It was in 2002, and he had been working for Yemen’s internal intelligence services for a while. In his early thirties, he was a “field” contact person for former Yemeni detainees who had returned from Afghanistan. His job was to monitor them and make sure that they would remain politically quiet after their return. The dictatorship of President Ali Abdullah Saleh was very close to the US government at the time, and an active ally in the “war on terror”. As he was in Egypt for a business trip, his day job was with a construction company; Abdul Al Salam was arrested and transferred to a prison where he remained for one and a half year. He did not know why he had been arrested and kept being asked about his involvement with al-Qaeda. He claims to have been tortured by Oman Suleiman in person, then head of the Egyptian Intelligence Services. In 2004, he was transferred to Bagram airbase and soon after shipped to Guantanamo. He has been there ever since, claiming his innocence among another ninety detainees from Yemen. While his family managed to make sporadic contact with him through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), they have no idea what his current situation is. They say he has been punished for a while, they don’t know why. Before the loss of contact, Abdul Al Salam wrote that there had been two assassination attempts made against him in Guantanamo. He also communicated to his family that they should never believe news of his possible suicide. In a Skype conversation organized by the ICRC, he said: “I will not commit suicide, don’t believe any of it. I know I am innocent. This is all game that is much bigger than me.” Was Abdul Al Salam sold to the US government, as his family seems to think? Was the information that he had so valuable that he deserved to be removed from the land of the living? In 2008, his two boys Omar, 11, and Yussef, 8, opened the safe where he was storing all the documentation related to his intelligence work. Due to the sensitive nature of his files, it was was booby-trapped. Both children died instantly. It was then up to his older brother Abdu Rahman to break the news to him, via the ICRC. Since the call was on humanitarian grounds, it lasted for two hours, and was overseen by a religious Imam. Abdul Al Salam was devastated. After costing him years of his life, his intelligence work had now killed his only children. Abdul Al Salam’s younger brother, Nabil, asks if detainees are human beings in the eyes of the US Government? He says that he had hope when President Obama was elected: he lost it very fast when he saw that Guantanamo’s announced closing was quickly forgotten about. Scores of journalists have interviewed him and his family for the past few years. Nabil still believes that those interviews can make a difference. Conversely, many Guantanamo families now refuse to meet journalists, since they believe that none of their testimonies amount to anything but boosting the profiles of the Westerners who “make it” to Yemen. High profile US lawyer David Remes took Abdul Al Salam’s case in 2005. He visited Sana’a on six occasions, and so far, there has been no progress. Abdul Al Salam is frustrated by what he calls Remes’ poor performance. He is even wondering if Remes is not a US spy. He wants to be represented by a new lawyer. As our meeting comes to an end, I ask both brothers if they believe that the new Yemeni government will stand up to the US regarding Guantanamo and other issues. I explain that many in the West believe that Yemen is now on the democratic path as a result of the so-called Arab Spring. Nabil replies: “it is like we are in a bigger prison than that of my brother, only ours is a little nicer.” According to him, only one entity can save his brother: God. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed