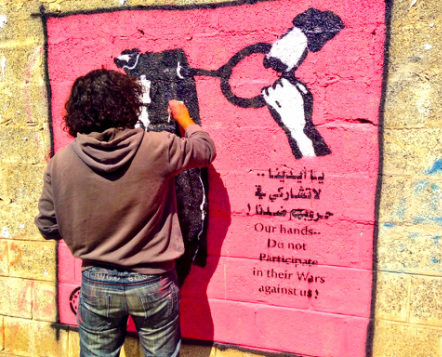

Murad Subay, 7th Hour, Twelve Hour Campaign, Sana'a Murad Subay, 7th Hour, Twelve Hour Campaign, Sana'a He is painting graffiti on a wall opposite a westernized shopping mall. All major media networks are there, Reuters, Al-Arabiya, Agence France Presse, they try to capture his attention as they are buzzing around him: “Murad, here please,” “Murad, Murad!,” “Hello Murad, can you explain what you doing;” a fixer approaches him as he tries to concentrate: “Murad, my client would like a bit of time to interview you later, can you make it?”… If twenty-seven year-old Murad Subay is a star, he does not behave like one. He does not see the circus going on around him as a disturbance, he embraces it and makes it part of his work. A self-made artist, he is painting to raise awareness on certain issues, and he channels the attention from his own person to the message he is trying to spread, both locally and globally. It is clear, vivid, uncompromising: two hands hold a hand-grenade circular safety pin, ready to undo it, a sentence is written both in Arabic and English “Our hands… Do not participate in their wars against us.” It all started in 2011, after the civil war that opposed dictator Ali Abdullah Saleh and other tribes, an offset of the “Arab Spring” which could well have transformed Yemen into another Syria. As opposed to Syria, the Yemeni dictatorship was backed by the US, and only a cosmetic change occurred: Saleh’s Prime Minister was elected in office with 99.6% of the vote.(1) Murad explains: “the city bore the scars of the clashes, so I went out and started to paint over them. After one week, people started to come and paint with me. Parents sent me their children, even soldiers put their weapons down and took brushes instead.” The Color the Walls of Your Street campaign was born. After to months, all major cities in Yemen took the initiative, colors appeared in Aden, Ta-az, Ebb, and Hodeidah. The campaign received international coverage, and was very well received by the Yemeni population. As Murad learned stencil art, his second campaign was planned. For some, it took a political turn, yet Murad stresses that it is not his aim: “we are not politicians and we don’t have power to stop what is happening to our country. The only thing we can do is making noise around important issues.” During seven months, every Thursday, faces of people “disappeared” by the government, some since the 1960s, were painted all over Sana’a and other towns. Next to the faces, the date of the disappearance, and the idea that no one can vanish from public view. Walls became a symbol of hope, of unity, not only for the disappeared but also their families, which were brought at the core of public spaces. The Walls Remember Their Faces campaign had a decisive impact. Maybe the US embassy asked that its puppet "ally" throw a bone to its people… Four months after the campaign started, Mutar Aleriani was released. He had been disappeared since 1981. He was tortured so badly with a drill that he can no longer move his legs. Confined to a wheelchair, he is not being looked after by his daughters. Murad met him in Hodeidah, his words against US ally Abdullah Saleh were understandably very harsh. Murad explains how the campaign has brought humanity onto the whole issue; meeting Mutar had a huge impact on him. Murad realizes that he cannot design a campaign for all the issues that Yemen is facing right now. He is not financed, and rejects all offers of help from international organizations, including the UN. He says that he needs to remain independent, so that the impact of his campaigns cannot be compromised: “the supplies could be coming from [not so benevolent neighbors] Saudi Arabia or Iran, we just cannot allow that.” Everyone who turns up brings their own supplies, and people who are part of the network also donate items randomly. Murad is his own complex adaptive system.(2) Paintings speak louder than academic lectures. Murad’s Twelve Hour campaign is now famous around the world for its coverage of the drones issue. A little boy writes right below a drone: “why did you kill my family.” This question is timely: many children in Yemen are asking themselves the question, day in, day out. Chances are that Westerner meeting them will be asked, just like I was.(3) Another painting by Hadel Almowafak represents a Tao symbol, on top the drone, and at the bottom a dove: the vivid imagery of Liberal Peace, the peace that kills innocents, the peace that I teach as pat of the UN. The drones representations figure in Murad’s Twelve Hours Campaign. Each hour of a clock brings in a new issue that Yemen is facing: weapons, sectarianism, kidnappings, poverty, and internal strife. Will one of the hours focus on Barack Obama’s war secret war against Yemen?(4) Murad’s stencils ought to reach the streets of Washington, D.C., New York and San Francisco, so that Yemenis would no longer be disappeared from the world’s view.(5) We often ask ourselves what we can in the face of injustice. Murad gives us a plain answer: noise. (1) See http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/25/world/middleeast/yemen-to-get-a-new-president-abed-rabu-mansour-hadi.html, accessed on January 20th 2014. (2) See Decolonizing Peace, chapter 3. (3) Please circulate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un0vxahkYFM (4) See http://dirtywars.org (5) For more information on Murad Subay and Hadel Almowafak, see: http://muradsubay.wordpress.com and http://hadeelalmowafak.wordpress.com

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed